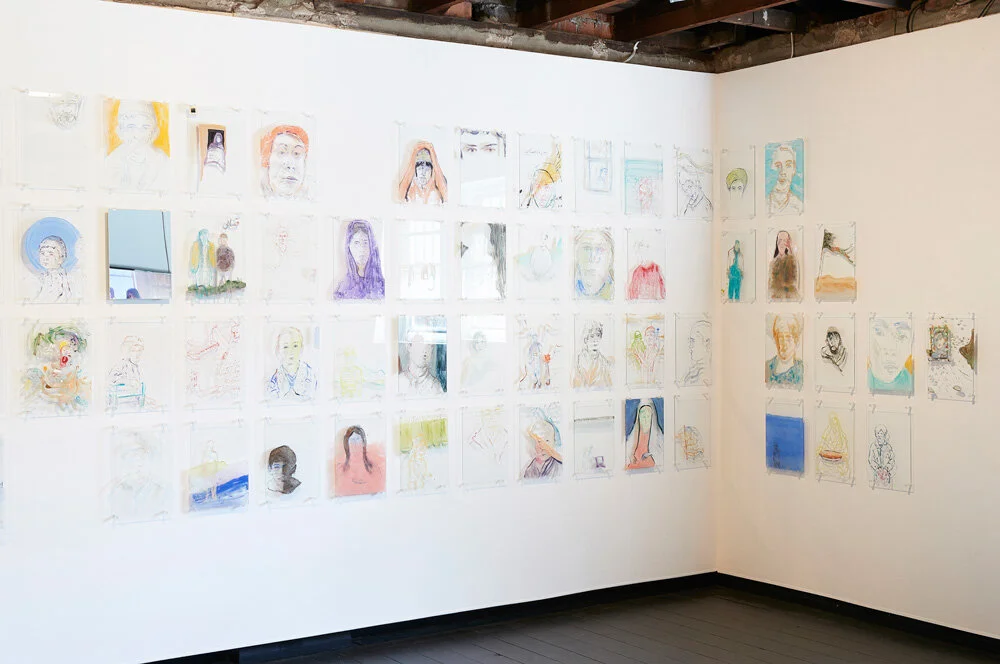

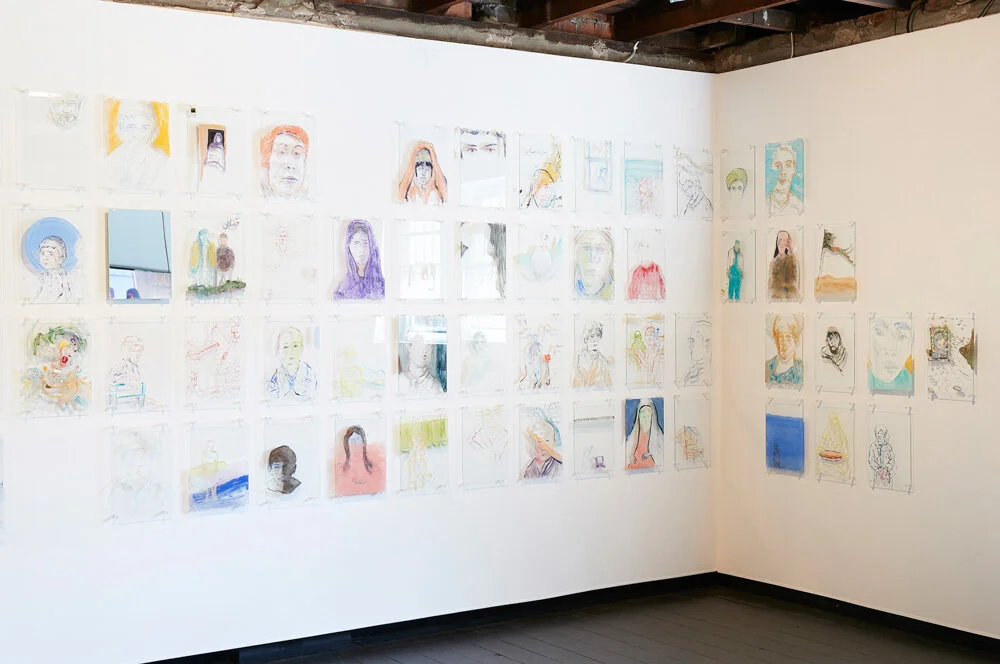

Elyas Alavi, Daydreamer Wolf, 2018, Firstdraft, Naarm (Melbourne). Photo: Zan Wimberley.

Elyas Alavi: Daydreamer Wolf

by Andy Butler

Commissioned by Next Wave x Firstdraft, Naarm (Melbourne) and ACE Open, Tarntanya (Adelaide)

Elyas Alavi’s practice engages in a process of auto-ethnography, where he connects his personal history and circumstances to broader cultural, social and political concerns. Daydreamer Wolf brings together first-hand experiences of conflict, war and displacement, and a questioning of the ways that these stories are staged for a Western audience, and the way that hope and longing figures into a life marked by displacement. Alavi is interested in the two-dimensional images of refugees and the Middle East that we use to make sense of the situation, to make decisions about belonging, to shape political outcomes, to maroon people offshore. His work navigates how lived experience figures into the narratives others tell about you.

The character of the ‘daydreamer wolf’ was created by Alavi in his first book of poetry in Farsi, I’m a Daydreamer Wolf (2008), where he walks the line between holding on to hope, longing for his homeland and family, and the feeling of being the eternal outsider - of living with a difficult past and hiding parts of himself from those around him. It was a time where he was forced to hide his Afghan background and Hazara ethnicity in Iran. It’s this space of tension between hope, one’s own difficult circumstances, and broader cultural narratives, that Alavi’s work inhabits.

From the perspective of a non-refugee audience in the West, hope, sympathy and compassion play a complex role in how we talk about displacement and war in the Middle East. The way we centre our own displays of compassion for the plight of the oppressed can obscure the realities of the circumstances that people face, and our complicity in structural distributions of power that help to maintain them. At the same time a distorted sense of compassion can play a function in a world view that supports off-shore processing and policies based on deterrence.

Where is Homeland? an installation of two paintings and a neon work, thinks critically about the ways that images of refugees circulate in the news and on social media. Alavi recreates front pages from The Weekend Australian and The Afghanistan Newspaper covering the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe – the same crisis that produced the image of three-year-old Syrian boy Alan Kurdi, dead on the shores of Turkey.

The work commands the audience to move close to the images, painted monochrome yellow in light brush strokes. It becomes clearer the closer you stand. These images stirred one of the biggest outpourings of sympathy from the West, on social media, in artworks, in donations to refugee organisations. It eventually fell out of the news cycle – several years since the temporary burst of support, little has changed, although Western governments have ramped up their involvement in wars in the Middle East.

A flashing neon sign spelling out where is homeland? in Farsi is a way to poetically speak to the displacement, longing and loss that persists outside of the media’s interest in the Middle East and refugees. In 2015, two of Elyas’s brothers made their way with their families through Europe, crossing eleven borders to eventually settle in Sweden. The monochrome yellow of the paintings serves a double purpose of both distorting our engagement with images that saturate the media, while also referencing the use of yellow in many non-Western cultures – a colour that symbolically refers to wisdom, holiness and purity. Alavi asks whether there’s a means of recasting the narrative of displacement that moves away from the mode of demonisation of asylum seekers, as he makes sense of his own very personal connection to the crisis. 113, a series of 113 portraits on glass, interrogates hope from another perspective. Alavi responds critically to mythology within the Shiite sect of Islam – the main religion of Hazara people – where a belief is held that a saviour will return to earth with 113 followers and bring justice and equality. Spread across both St Heliers Street Gallery and Chapter House Lane, some of the portraits are of Hazara people who have arrived in Australia as asylum seekers, and gone through our torturous offshore processing system, including Khodayar Amini, a Hazara man who, in October 2015 in Dandenong, burnt himself alive in protest, fearing he would be taken back into immigration detention and deported back to Afghanistan. The other half of the portraits are of causalities of a terrorist bombing in Kabul in 2016 that targeted a Hazara protest, which Alavi was caught in.

The ghostly images are doubled through the shadows they cast behind themselves. The series speaks to the sheer multitude of personal circumstances among Hazara people, that are as complex as and resonant with Alavi’s. The double images question the fractious connection between holding on to what Alavi sees as an unreal hope, and the oppression that Hazara people face both in the Middle East and Australia – of reaching out to a mythology of hope while living with the echoes of intergenerational oppression, conflict and displacement.

We die so that is a difficult video to watch. It shows Elyas’s own footage from the Kabul attack referenced in 113. It is confronting and demands attention from the viewer. It shows the brute reality of violence and oppression against Hazara people, and the attempt to determine the fate of a man missing after the attack, the coming together of people after violence. It places the artist as an involved witness to trauma and conflict. This sort of intimate and humanising footage is rarely seen in the West. Its positioning close to Where is Homeland? along with the sheer difficulty of watching it, forces us to question why we turn away from some narratives about the crisis, while others circulate freely.

There are other works in the exhibition – Salam, Khoobi? (hi, how are you?) and Naan, Salt, Pomegranate, Nafas – which gesture towards a type of hope that Alavi holds onto outside of the sensationalist narratives around refugees, or the mythological hope offered through religion. Both of these works sit in stark and quiet contrast to the images that come out of conflicts in the Middle East. Salam, Khoobi? seems relatively mundane – with several exceptions which speak to the constant fear of attack – offering an insight into the way that a scattered family tries to stay together. Naan, Salt, Pomegranta, Nafas pays homage to Middle Eastern poets, like Alavi, who write about dreams of peace in countries that have seen significant violence – single words from Alavi’s own and others’ poetry are placed close to suicide-bomb vests.

Alavi’s body of work deftly brings together a broad spectrum of emotions and experiences that come with a life of exile and conflict; of being cast as a ‘wolf’ by the media and governments in the West; and, in many ways, of feeling like an outsider in one’s own community. Through his multifaceted artistic and poetic practice, Alavi tries to find his own footing within a narrative that has been largely told by other people.

Image: Elyas ALAVI, Salt & Pomegranates, 2018-19, vest, salt, pomegranate, neon, light, 120 x 255 x 35cm, installation view, Daydreamer Wolf, ACE Open, 2019

— Andy Butler is an artist, writer and curator in Naarm (Melbourne). He is interested in how art-making and artistic history intersects with the ideological foundations of our political, social and economic institutions.

First published by Firstdraft: firstdraft.org.au